Abstract

Search engine results are a common challenge, especially for non-English languages. In this project, different models — including Google Search’s underlying transformer model (BERT) — are applied to improve the search engine of Denmark’s most significant job portal: jobindex.dk. The goal is to determine whether modern Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques can improve Danish-language search results. After comparing direct results amongst different models and methods, it’s possible to conclude that BERT excels. It’s incredibly successful on search queries that don’t usually return results or very long and complex queries since it’s based on word similarity.

Disclaimer

This report is unaffiliated with Jobindex.dk.

This report tries to be as non-technical as possible. However, some technical terms are impossible to escape. For the full code, visit here. Some terms are not detailed in-depth since that falls outside the core goal of this project and for a technical explanation or if you’d like this implemented in your company, get in touch. This report also involves knowledge of basic Danish.

Introduction

Searches are a recurrent challenge, regardless of the user and/or the company. Most entities rely on direct searches of terms. If you open your e-mail application and search for a specific text, you get what you searched for. If you searched for the word “receipts”, you’ll get emails that contain that exact same word.

But not all inquiries are black and white: sometimes you want semantically similar results too.

In the classical search engine — the non-AI and the most common today -, when performing a direct search, there’s no relation between words. The words in the search query will have to be present in the results, almost directly. Consider, for example, a job search using the query “psychiatrist” would return results with that same word. But you’d probably want to see results for jobs that include terms such as “psychiatry” and, perhaps on a lesser extent, “psychology”. Probably not on the top of the search results, but still very close to it.With the classical search approach, the chances of finding both with one search query are low.

And what about long search queries? There, the chances of getting noteworthy results with a direct search are meagre. In fact, the longer the query, the lower the chances of success.You shouldn’t need excellent search skills to find what you want.

However, recent advances in NLP techniques have allowed for transforming words into a common base form. For example, English words like “am”, “are”, “is” have their common form in the word “be” (a technique known as “Stemming”). They can also convert the plural of a word to it’s singular (known as “Lemmatization”). Here’s an example with both techniques: “The boys are eating pizza”, after being processed with the above methods becomes “The boy is eat pizza”.

But what is this good for? Well, applying these two techniques to documents will improve search results, finding similar results to our original search query. And those techniques are part of a few others used in this project, for a mostly Danish language dataset. This project benefits from how Danish NLP techniques have reached an outstanding level, paving the way for improved search results when compared to English language-based ones (typically more complete).

The relations between words are also important. Let’s take, for example (based on “Understanding searches better than ever before”). You’re searching for “2019 brazil traveller to USA need a visa.”. You’d probably get a result that includes the words “2019”, “brazil”, “traveller”, “USA” and “visa”. But the word “to” would be ignored in a direct type of search, since the word “to” it’s too generic. The word “to” changes everything in this, since it refers to where the person wants to travel to (from Brazil to the US). This results in very different outcomes of the search query, as you can see below:

It’s essential to convey that the results from the “before” image are powered by much more than just pure term match.

But there are more hurdles to this then word relations. There’s also the handling of different languages. Non-English languages pose a challenge since there’s not as much data to train Machine Learning models when compared to the English language.

However, recent breakthroughs allow having good model results, even in multilingual approaches, including Danish. That’s where BERT comes in. BERT is “a neural network-based technique for natural language processing (NLP) pre-training called Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers”. This model allows for a contextual representation of words, meaning that context matters when doing searches and an excellent example for that is the one from above. In that example, not only the individual words are important but also its relation to the other words in the same search query. Plus, when taking the word “to” into account changes the accuracy of these results.

All in all, the above techniques set the foundations for this project as they are part of a toolset to make search engine results better by using document similarity.

In short, in this project, we are comparing results from the models (both AI-based and not) and the current results given in the Jobindex.dk’s website. We are determining how AI leverage existing document searches, even for non-English languages, such as Danish.

Methodology

Dataset

The dataset is comprised of 4.2m jobs from jobindex.dk, from 2000 until March 2020.

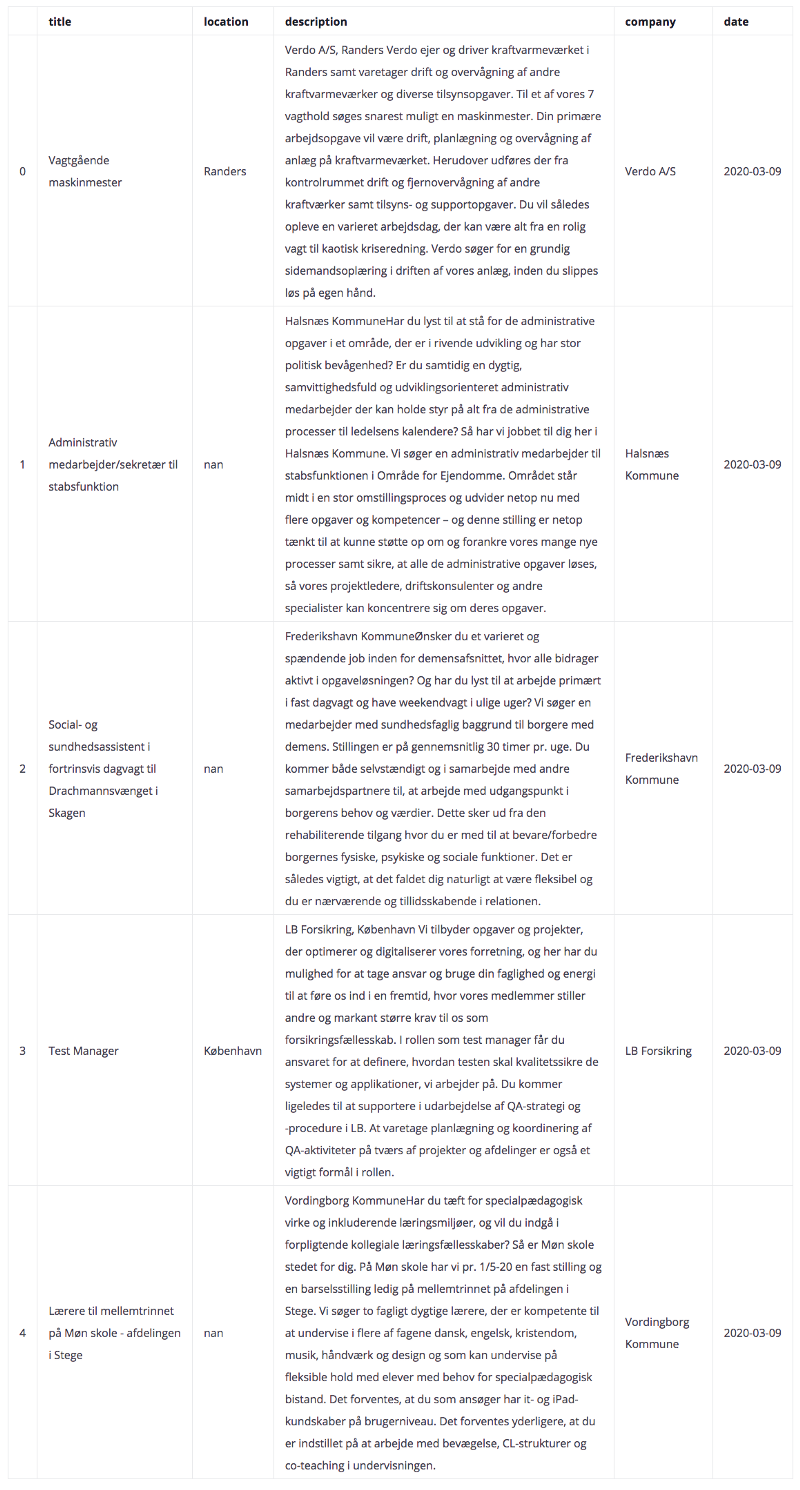

Here’s an excerpt of the dataset:

Title, location, description and date are some of the features in the original dataset. The remainder is excluded since they don’t provide a signal to the project at hand. Some of the entries have empty rows for certain features, due to some difficulty upon scraping the data.

Hardware

The computations are made in a Macbook Pro 2016 model.

Preprocessing

The preprocessing included several subtasks:

- Lower casing of words

- Lemmatization

- Stemming

- Removing stop words in Danish

Apart from lemmatization and stemming — already explained in the Introduction — it’s necessary to remove stop words. Stop words are common words in a given language. Some of the danish stop words are:

'og', 'i', 'jeg', 'det', 'at', 'en', 'den',

And the list goes on.

Since some job titles and descriptions are in Danish and others are written in English, it was a challenge to differentiate each, so that the preprocessing occurred separately for both languages. There are a few possibilities here to distinguish languages, such as using a language detector, but it is something left for a future iteration of this project.

Techniques and models used

Direct search

Direct search is a simple search based on query terms. As mentioned above, if you search for the word “teacher”, you’ll get the results regarding job titles that have the same word included. There are no variances to this.

Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TFIDF)

This numerical statistic determines the number of times a word appears in a document, balanced by the inverse number of documents where that word appears. A word that often appears in one document would be balanced by how many documents it occurs. Considering TFIDF returns a value if you have a word that occurs once in many different documents and another that appears many times in the same document, they would have very similar values.

In this project, this is calculated for every single word of the dataset. Of course, each word will have its own vectorial representation — the denominated “word embeddings” (further reading).

TFIDF is a technique that assesses a word without its context. It also depends on the results of Direct Search, since it finds its closest job titles based on the direct results. If no direct results are returned, then TFIDF will also not return any result. This has to do with the way TFIDF is calculated since it always depends on the total number of word occurrences throughout the dataset.

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT)

BERT is a pre-trained open-source language model, as an outcome from a paper published in 2018 by the researchers at Google. BERT introduces a bidirectional contextual approach. Simply put, it looks at a sentence and its context by “reading” it from left to right and right to left and converts into vectors (“embeddings”). Further reading here.

Model assessment

By creating the vectorial representation of job postings, it’s then possible to compare how similar than are with one another. This similarity is determined via ‘cosine similarity’ (Further reading here) and all the distances are stored in a distance matrix.

Results

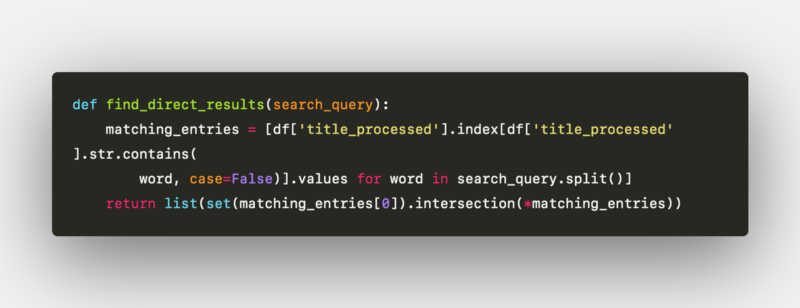

The results results from the actual jobindex.dk website are then compared with direct search, TFIDF and BERT techniques. The direct search is a very simple approach to return direct results, as explained before. Without going into details, it’s limited into one algorithm in this project:

Direct Search results algorithm

Today there are very advanced techniques and libraries that work very well. As mentioned before, the goal is to determine whether AI can leverage existing search techniques.

However, it was not possible to perform computations on the whole dataset due to its size. It’s because when storing the distances between vectors from TFIDF, it creates a distance matrix of 4.2m rows x 4.2m column (resulting in 1.764e+13 cells), making it impossible to store on the disk of the current machine used and virtually impossible to store in memory on any common machine. A possibility to tackle this challenge is presented in the “Future Improvements” chapter later on.

The short-term solution was to create a slice of the original dataset. Thus, a dataset comprised of all the datasets between 2020–02–26 and 2020–03–26 (inc.) is created, which results in a dataset with the size of 10140 job postings.

BERT, on the other hand, was handled in a slightly different way than the TFIDF approach. A file with all the embeddings is created and later on imported into memory. The reason why the last step before getting recommendations from BERT is handled in memory is because of its internal optimizations (since it uses tensors, instead of regular arrays). These optimizations make it much faster to run in memory. Being able to quickly load and sort a dataset of around ten thousand rows is one of the advantages from BERT when compared to TFIDF. Of course, for bigger datasets, a better form of handling would be to have disk persistence.

The github repository shows the preprocessing in detail.

A few different types of examples of job searches are used to compare the different approaches. A concise query term is the first example, followed by a medium (2 words) and finished by a long query (3+ words), as shown below:

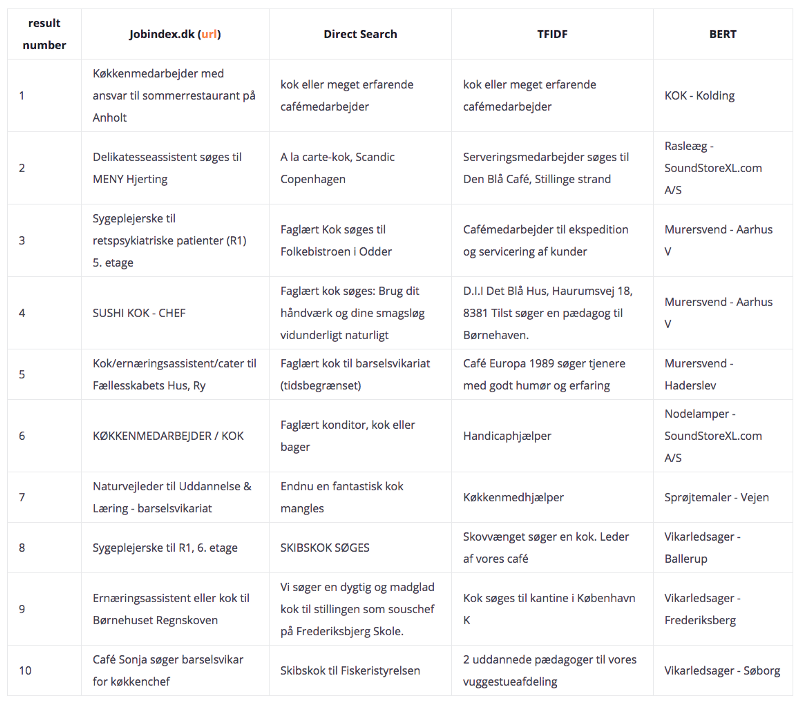

Example 1 — “kok”:

This search query translates as “chef”.

In this example, all models are compared, including also the results from Jobindex.dk, limited to a maximum of 10 results. As a reminder, below are the results of the subset of data. So, for this query, the results are:

Several conclusions are drawn from studying the first results table:

- The results from Jobindex.dk are not bad, since a few of them include the word “kok” or “køkken”. However, they are not in order. Also, they are interspersed with unrelated job titles, such as “Sygeplejerske” on result #3 and #8.

- Direct search (using the algorithm above) presents quite good results. All of the results include the word kok.

- TFIDF presents relatively good results, but some noise as well.

- BERT returns a lot of noise, with only one good result.

The main reason for the TFIDF and BERT present noise is because when they are processed, the description of the job postings is included. Some descriptions are not representative of the actual job title. However, the Direct Search results do not include job descriptions, hence the good results. But what happens when search queries become more specific and more complex? Let’s take two more examples.

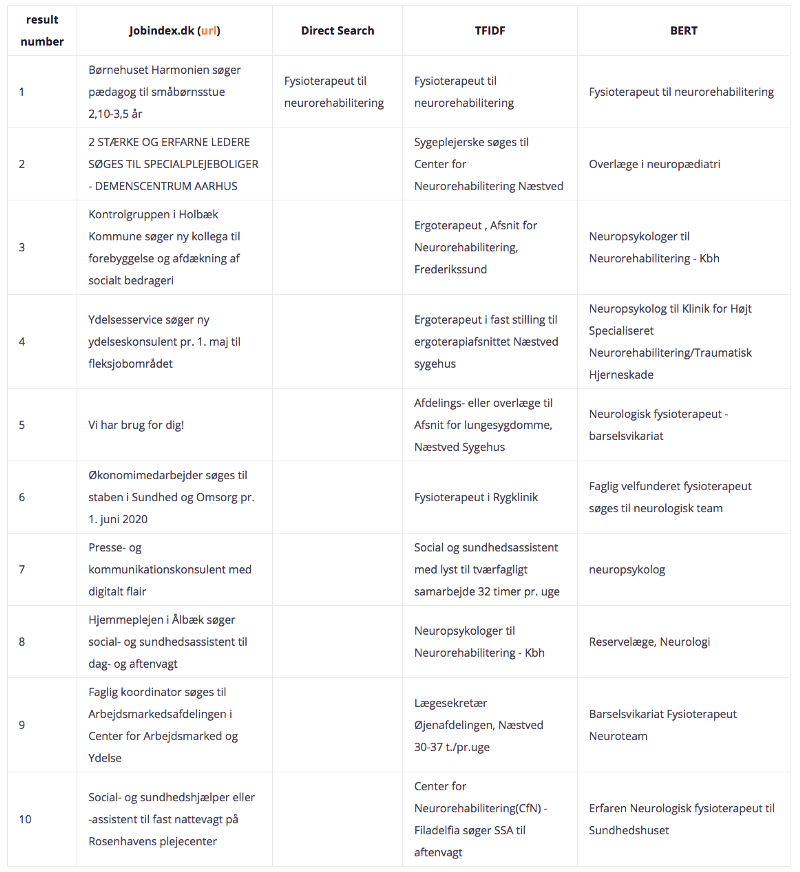

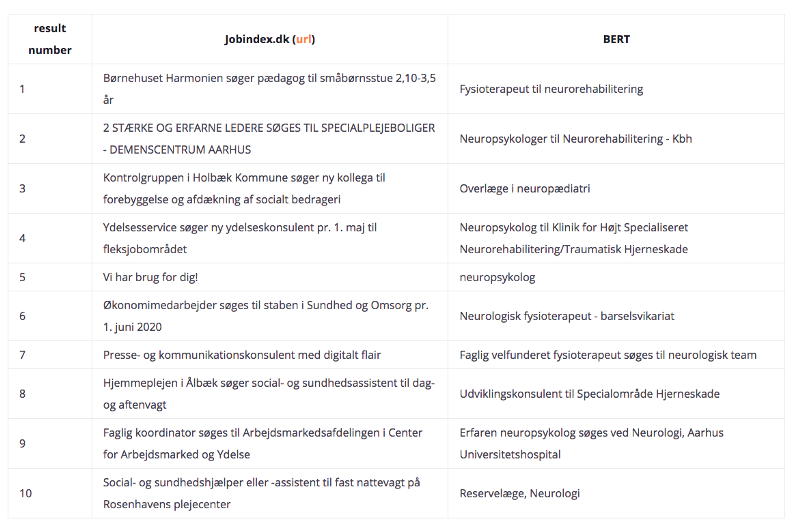

Example 2 — “Fysioterapeut til neurorehabilitering”:

When the search query (“Fysioterapeut til neurorehabilitering”, in this case) starts getting longer, a few interpretations can be drawn, shown in the table above:

- A few results returned via Jobindex.dk are irrelevant. The remaining results are in the health sector but still somewhat distant from the actual query.

- Direct Search returns one result only since all the terms in the query are present in Direct Search results, but not more than those. This Direct Search result does not appear in the Jobindex results.

- The first result from TFIDF is the actual query. The remainder of the results is also quite relevant since they revolve around Neurorehabilitation and/or Therapists. It’s the first example where we get similar results to the actual query, without using words from the initial query.

- BERT also presents outstanding results. The first result matches the query and subsequent results demonstrate variations of the word “neurorehabilitering”, such as “neuropædiatri”, “Neurologi”,”Neuroteam” and “Neurologisk”.

It’s now possible to see that BERT exceeds in the quality of returned results. Specifically, the word “neurorehabilitation” is the area of expertise.

On the other hand, TFIDF revolves around variations of the profession, hence losing track of what matters, which is the “neurorehabilitation” sector. But let’s see two examples where BERT exceeds on a more significant margin.

Example 3 — “Tekniker til neurorehabilitering”

This query roughly translates to “Technician for neurorehabilitation”. With this query, there are no Direct Search results, hence no TFIDF results. For that reason, the table below omits Direct Search and TFIDF columns.

This is were BERT vastly exceeds: on top of actually returning results (compared to the previously mentioned approaches), it yields very relevant job titles. It also vastly exceeds the quality when compared to the Jobindex.dk results.

The word “til” (“for”) in the query again influences the query results since what we want is a technician within a specific area. Thus, having results such as a physiotherapist, doctor or psychologist are quite relevant while still being under the Neurorehabilitation topic.

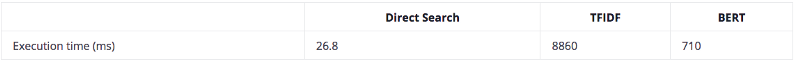

Performance comparison

For this example, we’re using the search query “Børne”. It’s a generic query to guarantee direct search results and TFIDF results, thus making it possible to perform comparisons.

The BERT model always returns results. Instead of analysing which of the models returns results, we’re going for the time it took to execute them. This performance is still assessed on the 10140 job postings sub-dataset.

Below are the execution times compared:

BERT exceeds TFIDF by a large margin. As expected, Direct Search is the fastest. However, Direct Search does not usually return relevant results, only the what words you search is what words you get. The execution times can be decreased with better memory optimisation and avoiding doing calculations in memory as much as possible.

Where BERT excels

Alongside the fact that BERT finds results on similar words, it also performs strongly on searches with typos and locations.

In the following example, a new sub-dataset of 273585 job postings was used. As a reminder, the previous sub-dataset has 10140 job postings. Since we’re not using TFIDF in the following example, it becomes much faster to create and read all the word embeddings, making BERT much more performant than other models (as shown previously).

In this example, we’re searching for results for the query “advokat til ejendomme i Copenhagen”. It is a mix of English and Danish, it includes a location, and the most important keyword is “ejendomme” (and not “advokat”). That’s because we use the “til” word in the search query hence changing priorities for our results.

Here are the top four results:

- Jurist med speciale i fast ejendom til Københavns Ejendomme og Indkøb

- Jurist med kendskab til erhvervslejeret og fast ejendom til Udlejning i Københavns Ejendomme & Indkøb

- Jurist med kendskab til erhvervslejeret og fast ejendom til Udlejning hos Københavns Ejendomme & Indkøb

- Advokatfuldmægtige til København

When it comes to relevance, there’s a clear distinction between “ejendomme” and “advokat”. “Jurist” results appear on top since what we want is the area of expertise and not the profession itself. In the last place, we have the “advokat”-related result. It’s noticeable that the results prioritise Copenhagen too: even though the location in search query was in English, the results returned contain the word “Københavns/København”.

Limitations and Future improvements

One of the limitations is the processing power limited to the current machine used in this project. A more powerful machine will overcome some of the difficulties, thus allowing future improvements on all of the approaches taken above.

Another limitation was the quality of the description of the job titles. Despite that the results are only focusing on the job titles, its description is still relevant to achieve better embeddings. However, its quite often that the job descriptions don’t represent job titles as such, thus creating noise in the data. It’s an explainer for some of the non-relevant results.

Although the results are promising, especially using BERT, there’s still room for improvement, such as:

- Improve direct search algorithm. Can be done by leveraging existing technologies that handle search which will allow for better and more performant direct search results. Here’s an example of BERT on top of Elasticsearch

- Train BERT. This project uses a pre-trained BERT algorithm. Training BERT with the Jobindex data will most certainly yield better results.

- Improve model assessment. Currently, the model performance is assessed on a common sense basis. For example, if we search for “fysioterapists” and one of the results is “cook” then it’s possible to infer that the result is not good. This observational research can — and should — be evaluated in a more quantitatively way. If the model is trained using the Jobindex dataset (as suggested before), it will give a better numerical insight on how strong it is performing (by knowing how well it generalizes).

- Avoid using memory for calculations. In order to get results, the preprocessed datasets were loaded into memory. Ideally, they should not for performance reasons so that a solution can be storing the results (the embeddings and the similarities) in a database. Alternatively (and probably ideally) the best solution is to serve the custom trained BERT model.

- Improve language distinction. The preprocessing step includes handling danish text. However, some job postings and its descriptions are in English as well. Mixed-language job postings make it harder to preprocess its text. To not use preprocessing text techniques on the wrong language, there should be a better distinction between languages. This can be done in many different ways, being one of them adding a new column to the dataset that includes the language in question. It still doesn’t solve the issue of job postings where the title is in Danish (for example) and the description in English, or vice-versa. Or the cases were the job description is mixed-language.

- Improve variations of search queries. A commonly used word in the search queries of this project is “til”, and future tests should have a broader range of conjunctions.

Conclusion

The goal of this project was to determine whether AI can be used to improve search on Danish-language documents. The results show that not only a Deep Learning-based algorithm matches conventional search techniques but drastically enhances those. It excels on long and complex queries and finds results on cases where classical search finds none.

Moreover, using a few approaches, it’s possible to infer that BERT -

Google’s underlying search Deep Learning algorithm — understands not only similar searches terms but also its context. All while performing exceptionally well on non-English languages.

Hopefully, this project paves the way to success for companies struggling with document search in Danish. It conveys the message that AI doesn’t need to be a replacement to current search engines but rather the combination of both, which allows improving a search engine from adequate to excellent.